|

|

|

George's Wild West Adventure |

George

Blunderfield was born in Hales, Norfolk on the 29th August 1829 and

was the second eldest in a family of twelve children born to Francis and Mary

Ann Blunderfield. The family farmed at Hales Hall Farm just a couple of miles

from Loddon. One of their neighbours, at Bush Farm, was Matthew Atmore and his

family. Children from both families would, at some point, have attended school

in Loddon, probably travelling to/from school together and no doubt becoming

friends. Certainly George and Charles Atmore were known to each other, a

friendship that continued when they both moved to Norwich around 1840 for more

advanced education. Charles’ father, Matthew, was a local preacher in the

Methodist Church and believing he could do better in America, crossed the ocean

in 1844 with his family aboard the "Mediator", a sailing-vessel under

the command of Captain Chadwick. The voyage started on the 17th March and landed

in New York after twenty-three days on the ocean. Eventually settling in Calhoun

County, Michigan on a farm near Battle Creek, with eighty acres of timber land

and a snug little frame house. Whether George travelled out with them in 1844 is

not known but he certainly joined them at some point as he appears in the 1850

US Census, working on a farm in Convis Township just a few miles from the home

of Charles in Pennfield Township.

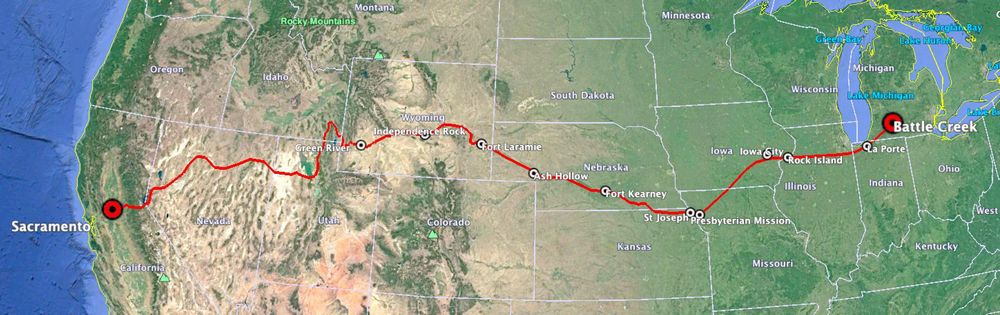

By

the spring of 1851 gold fever had been in full swing for two years, following

the initial ‘rush’ of the 49ers into California. George, and his friends

Charles, Richard and John Atmore, were clearly attracted by the 'get rich

quick' stories and made plans to head for California Charles had about

$300 but George and the two younger Atmore boys only had $100 each. With a

four-horse team and wagon, they left Battle Creek on the 22nd March 1852 .and

travelled through La Porte, Indiana, across Illinois, going south of

Chicago, then on to Rock Island where they could ferry across the Mississippi.

The mud was axle deep all the way to St. Joseph, Missouri. They crossed the

corner of Iowa near to where Iowa City now stands - at that time marked by a

lone log house. With their rifles, they were able to supply themselves with

game. Until they reached Iowa, they had stayed in houses each night but they now

had to begin camping out, either by a small stream, or in a little grove. On

their first night in Iowa, being afraid of Indians, they slept in the wagon,

with feet to feet, and guns by their sides. During the night George aroused the

others, saying Indians were near, and Charles was about to shoot, when he

discovered the noise was caused by one of their horses. Many a joke was cracked

about the Indians they had seen, and George was not allowed to forget his

mistake.

By

the spring of 1851 gold fever had been in full swing for two years, following

the initial ‘rush’ of the 49ers into California. George, and his friends

Charles, Richard and John Atmore, were clearly attracted by the 'get rich

quick' stories and made plans to head for California Charles had about

$300 but George and the two younger Atmore boys only had $100 each. With a

four-horse team and wagon, they left Battle Creek on the 22nd March 1852 .and

travelled through La Porte, Indiana, across Illinois, going south of

Chicago, then on to Rock Island where they could ferry across the Mississippi.

The mud was axle deep all the way to St. Joseph, Missouri. They crossed the

corner of Iowa near to where Iowa City now stands - at that time marked by a

lone log house. With their rifles, they were able to supply themselves with

game. Until they reached Iowa, they had stayed in houses each night but they now

had to begin camping out, either by a small stream, or in a little grove. On

their first night in Iowa, being afraid of Indians, they slept in the wagon,

with feet to feet, and guns by their sides. During the night George aroused the

others, saying Indians were near, and Charles was about to shoot, when he

discovered the noise was caused by one of their horses. Many a joke was cracked

about the Indians they had seen, and George was not allowed to forget his

mistake.

The Missouri river at St. Joseph was so high that they had to wait ten days

before they could cross. St Joseph was a bustling but rough frontier town, the

last supply point before heading out to the ‘Wild West’, so it was no

surprise that during the wait, there had congregated about one thousand wagons,

four or five thousand horses and mules, and about the same number of people, of

all classes and dispositions. They crossed the river on the 10th May but with so

much traffic the tracks had become very muddy. All along the road they passed

wagons stuck in the mud but they travelled without accident, each one wading

through, sometimes waist deep, with a shoulder to the spoke.

In

Nebraska they came across a camp of Sac and Fox Indians on a little stream,

who had built a bridge and demanded $1 per head to cross it. About

twenty-five miles north-west of St. Joseph they came to the Iowa Presbyterian

Mission, where there was a stockade and some outbuildings. Another traveller in

1852, John Clark, was relieved to find a blacksmith there to mend his broken

wagon and describes a large farm under excellent cultivation with a store and a

schoolhouse where they taught young Indians. Except for forts, these were the

last buildings they would see until they reached Nevada.

In

Nebraska they came across a camp of Sac and Fox Indians on a little stream,

who had built a bridge and demanded $1 per head to cross it. About

twenty-five miles north-west of St. Joseph they came to the Iowa Presbyterian

Mission, where there was a stockade and some outbuildings. Another traveller in

1852, John Clark, was relieved to find a blacksmith there to mend his broken

wagon and describes a large farm under excellent cultivation with a store and a

schoolhouse where they taught young Indians. Except for forts, these were the

last buildings they would see until they reached Nevada.

Some twenty miles west of the Iowa Mission they came to a deep swamp, where they

found in abundance, bacon, corn, oats, etc., left by those who had overloaded

their wagons. All who needed helped themselves. They crossed the Big Blue which,

having steep and muddy banks, was difficult to cross, and for some distance it

was deep swimming. When they reached the Little Blue, they turned to the north

to avoid crossing. During their journey they came across many discouraged men

returning east, but these kept off to one side as much as possible on account of

the jeers with which they were greeted. On reaching Fort Kearney they learned

that a Sioux Indian, who had been captured by the Pawnees, had been in training

to run for his life, a 'privilege' that had been secured by the United States

government. The Indian had acquired great speed, and to watch the race, a great

company of Indians had been brought together.

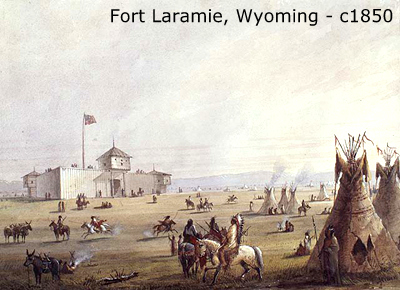

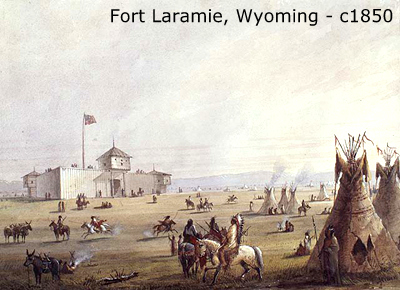

From Fort Kearney, the party went

along the south fork of the Platte and crossed at a point where the river was three-quarters of a mile wide

but had quicksand. Heading North to Ash Hollow and a steep descent to the North Platte

River which they followed north-west to Fort Laramie. The Platte rivers were

silty and muddy so camps were often made close to the tributaries that had

fresher water. However, with so many people using these camping sites the water

became contaminated and Cholera was prevalent. They saw many newly made graves

and 15 miles south of Ash Hollow they met a company of men digging a grave in

the road in which they were to bury their father (the earth in the road would

become compacted and difficult for Coyotes to dig up). Every day for a month they saw human bones along the trail that had

been dug out by the coyotes..They found Fort Laramie a lovely place, in a

beautiful location. Between Fort Kearney and Fort Laramie the roads were

excellent and game plentiful.

From Fort Kearney, the party went

along the south fork of the Platte and crossed at a point where the river was three-quarters of a mile wide

but had quicksand. Heading North to Ash Hollow and a steep descent to the North Platte

River which they followed north-west to Fort Laramie. The Platte rivers were

silty and muddy so camps were often made close to the tributaries that had

fresher water. However, with so many people using these camping sites the water

became contaminated and Cholera was prevalent. They saw many newly made graves

and 15 miles south of Ash Hollow they met a company of men digging a grave in

the road in which they were to bury their father (the earth in the road would

become compacted and difficult for Coyotes to dig up). Every day for a month they saw human bones along the trail that had

been dug out by the coyotes..They found Fort Laramie a lovely place, in a

beautiful location. Between Fort Kearney and Fort Laramie the roads were

excellent and game plentiful.

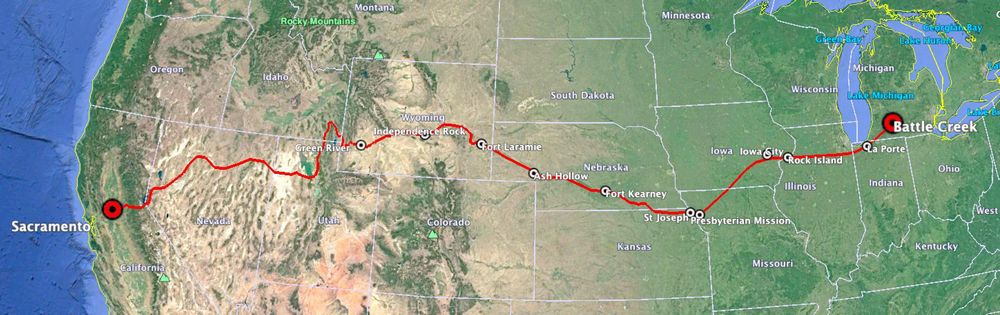

Their route from Fort Laramie followed the North

Platte upstream passing what is now Casper and then turned south-west to find

the Sweetwater River. Here they came across

one of the most significant landmarks of the trail - Independence Rock. Many

travellers aimed to arrive at Independence Rock no later than the 4th of July,

to be sure of reaching California (or Oregon) before snow came in the Rockies

and closed the trails. They followed the meandering Sweetwater westwards,

crossing it seven times in one half day. Leaving the Sweet Water, the men

travelled over the country to the Green River, which was so high that a man had

been drowned the day before they reached there. However, they forded it

successfully, pulling the wagons across with ropes and carrying provisions

across on horseback.

They had crossed the Continental Divide at Pacific Spring, but were unconscious of

the fact until one day, when they discovered the stream flowing in a different

direction.

The next important stream was

Bear River in Colorado, which they ascended till they reached Soda

Springs. There they found Indians encamped, in the hope of trading horses for

powder and tobacco, but as the party had neither of these articles, they gave

the red men a wide berth. However, a few days later came across some Indians who

proved to be friendly and with whom they travelled for a time along the Raft

River. The party arrived at Thousand Spring Valley on Saturday the 3rd of July

and camped out, it being their rule not to travel

on Sunday. The next morning, about ten o'clock, they were visited by two

Indians, who begged for food and after eating laid around the camp for several

hours. When it was time for Charles to go on guard, he heard the neighing of

horses and found that the Indians had stampeded their horses and were rolling

stones off the divide in order to keep the animals excited. Charles and George

at once began to pursue the Indians and followed them until one o'clock at

night. When they reached the divide the wind was high and the night so dark it

was impossible to pursue their way, so they were obliged to turn back to camp.

On their way they heard a bell which they judged to indicate that Indian ponies

were near. They threw rocks at the object, and soon men approached, with a very

forcible salutation, inquiring what they were doing. After some parley they

found friends. As soon as possible they made their way back to camp, five miles

distant. The camp was soon astir and preparing breakfast for those who started

at day-break in search of the horses. The men went to the divide and soon saw

the horses, a quarter of a mile away. When they reached the place there was but

one Indian; they concluded the other had gone for help. The Indian jumped on the

back of his pony and lassoed one horse, but it pulled back, giving the men an

opportunity to catch up with him. He finally was obliged to cut the rope. With

four of the horses the men started back toward camp. Soon about twenty-five

Indians were pursuing them but they found friends and were able to get to their

wagons and out of danger.

The party next had to cross forty miles of desert in

Nevada, where they saw Oxen, still in their yokes and chains, lying where they

had fallen dead from thirst. The winds in the desert were so strong that it blew

the cover of their wagon. Soon after crossing the desert their provisions were exhausted but fortunately

they succeeded in getting some that had been sent out from California by the

state government and in Carson Valley they found a Mormon settlement. They

camped in a beautiful grove of cottonwood trees, where they found many others.

It was there that one member of the party died and was buried in the middle of

the road, with suitable funeral services. When on the Sierra Nevada they sold

their teams for $500 in gold, with the privilege of using them for the next

seventy-five miles to Mud Spring, in Eldorado County, California. There they

turned the teams over and took their blankets, sleeping in these for one night

in a barn. At dawn the following morning, the original party of four set out to

visit Stephen Gilson, better known as “Squire Gilson”, a friend from

Michigan, who had a ranch in Coloma near Sacramento. Now walking, their progress

was slow and it took them three days to cover the twenty-five miles. After a

week there they went on to Sacramento and decided to split up, their remaining

money was divided equally among the members of the company.

They arrived in California in August. It had taken them almost 5 months to

complete the journey of 2,100 miles across America.

The movements of George Blunderfield from this point are not known. The

biography of Charles Atmore, written around 1900, from which the above text has

been formed makes no further mention of him by name but there are further

references to ‘a friend’ – it is possible that he stayed in touch with

Charles and accompanied him on other journeys. The next recorded appearance of

George is in 1860, arriving by sea at a port in Ohio in 1860 – but from where?

Between 1860 and 1863, George returned to England and Norfolk, where he married

Anna Maria Spurgeon and began farming at Church Farm, Heckingham. They had no

children but I'm sure other children in the village would have been enthralled

by the stories he could tell of his 'Wild West' adventures. George died on the

4th November 1886 aged 57.

It is known that George’s friend, Charles Atmore, had a variety of jobs in

California from which he accumulated $3,000 before returning to Michigan towards

the end of 1853. This journey was made, mainly by sea via Nicaragua and New

York, at a cost of around $400. In Michigan, he bought twelve horses to take to

California and started upon his second overland trip in March 1854. During this

stay in California, Charles engaged in mining. However, in 1856, with about

$1,500 he had saved, he returned to Michigan again, this time via the Isthmus of

Panama (as the Panama railway had opened in 1855). The steamer took fire in mid

ocean but the fire was extinguished. He bought land and married soon afterwards.

NOTES

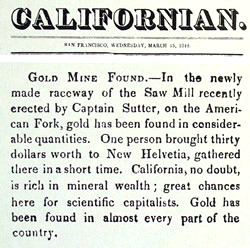

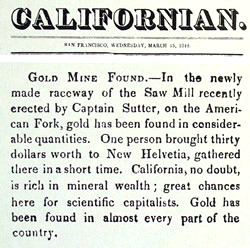

(1) In

1846, the population of the territory that is now

California

was estimated to be around 14,000 (of which 2,500 were in

Pueblo

de los Angelos). The discovery of gold in 1848 at Columa and the extraordinary

richness of the deposits, startled the civilized world and initiated the ‘gold

rush’ (the 49ers). In just over 4 years, the huge influx of

emigrants and gold seekers had swelled the population to 314,000,

enabling the territory to become a full member of the

United States

.

By

the spring of 1851 gold fever had been in full swing for two years, following

the initial ‘rush’ of the 49ers into California. George, and his friends

Charles, Richard and John Atmore, were clearly attracted by the 'get rich

quick' stories and made plans to head for California Charles had about

$300 but George and the two younger Atmore boys only had $100 each. With a

four-horse team and wagon, they left Battle Creek on the 22nd March 1852 .and

travelled through La Porte, Indiana, across Illinois, going south of

Chicago, then on to Rock Island where they could ferry across the Mississippi.

The mud was axle deep all the way to St. Joseph, Missouri. They crossed the

corner of Iowa near to where Iowa City now stands - at that time marked by a

lone log house. With their rifles, they were able to supply themselves with

game. Until they reached Iowa, they had stayed in houses each night but they now

had to begin camping out, either by a small stream, or in a little grove. On

their first night in Iowa, being afraid of Indians, they slept in the wagon,

with feet to feet, and guns by their sides. During the night George aroused the

others, saying Indians were near, and Charles was about to shoot, when he

discovered the noise was caused by one of their horses. Many a joke was cracked

about the Indians they had seen, and George was not allowed to forget his

mistake.

By

the spring of 1851 gold fever had been in full swing for two years, following

the initial ‘rush’ of the 49ers into California. George, and his friends

Charles, Richard and John Atmore, were clearly attracted by the 'get rich

quick' stories and made plans to head for California Charles had about

$300 but George and the two younger Atmore boys only had $100 each. With a

four-horse team and wagon, they left Battle Creek on the 22nd March 1852 .and

travelled through La Porte, Indiana, across Illinois, going south of

Chicago, then on to Rock Island where they could ferry across the Mississippi.

The mud was axle deep all the way to St. Joseph, Missouri. They crossed the

corner of Iowa near to where Iowa City now stands - at that time marked by a

lone log house. With their rifles, they were able to supply themselves with

game. Until they reached Iowa, they had stayed in houses each night but they now

had to begin camping out, either by a small stream, or in a little grove. On

their first night in Iowa, being afraid of Indians, they slept in the wagon,

with feet to feet, and guns by their sides. During the night George aroused the

others, saying Indians were near, and Charles was about to shoot, when he

discovered the noise was caused by one of their horses. Many a joke was cracked

about the Indians they had seen, and George was not allowed to forget his

mistake. In

Nebraska they came across a camp of Sac and Fox Indians on a little stream,

who had built a bridge and demanded $1 per head to cross it. About

twenty-five miles north-west of St. Joseph they came to the Iowa Presbyterian

Mission, where there was a stockade and some outbuildings. Another traveller in

1852, John Clark, was relieved to find a blacksmith there to mend his broken

wagon and describes a large farm under excellent cultivation with a store and a

schoolhouse where they taught young Indians. Except for forts, these were the

last buildings they would see until they reached Nevada.

In

Nebraska they came across a camp of Sac and Fox Indians on a little stream,

who had built a bridge and demanded $1 per head to cross it. About

twenty-five miles north-west of St. Joseph they came to the Iowa Presbyterian

Mission, where there was a stockade and some outbuildings. Another traveller in

1852, John Clark, was relieved to find a blacksmith there to mend his broken

wagon and describes a large farm under excellent cultivation with a store and a

schoolhouse where they taught young Indians. Except for forts, these were the

last buildings they would see until they reached Nevada. From Fort Kearney, the party went

along the south fork of the Platte and crossed at a point where the river was three-quarters of a mile wide

but had quicksand. Heading North to Ash Hollow and a steep descent to the North Platte

River which they followed north-west to Fort Laramie. The Platte rivers were

silty and muddy so camps were often made close to the tributaries that had

fresher water. However, with so many people using these camping sites the water

became contaminated and Cholera was prevalent. They saw many newly made graves

and 15 miles south of Ash Hollow they met a company of men digging a grave in

the road in which they were to bury their father (the earth in the road would

become compacted and difficult for Coyotes to dig up). Every day for a month they saw human bones along the trail that had

been dug out by the coyotes..They found Fort Laramie a lovely place, in a

beautiful location. Between Fort Kearney and Fort Laramie the roads were

excellent and game plentiful.

From Fort Kearney, the party went

along the south fork of the Platte and crossed at a point where the river was three-quarters of a mile wide

but had quicksand. Heading North to Ash Hollow and a steep descent to the North Platte

River which they followed north-west to Fort Laramie. The Platte rivers were

silty and muddy so camps were often made close to the tributaries that had

fresher water. However, with so many people using these camping sites the water

became contaminated and Cholera was prevalent. They saw many newly made graves

and 15 miles south of Ash Hollow they met a company of men digging a grave in

the road in which they were to bury their father (the earth in the road would

become compacted and difficult for Coyotes to dig up). Every day for a month they saw human bones along the trail that had

been dug out by the coyotes..They found Fort Laramie a lovely place, in a

beautiful location. Between Fort Kearney and Fort Laramie the roads were

excellent and game plentiful.