|

|

|

Life and death on the High Seas |

Thomas

Blunderfield was born in April 1781, the twelfth child

of Thomas, a yeoman farmer of Heckingham, and his wife Martha. Three previous

sons had been named Thomas but each had died in infancy. He would certainly have

worked on the family farm as a young boy but as the youngest of five surviving

sons there would have been no prospect of him inheriting the farm and would need

to seek other work to gain an independent income. Whilst in the nearby coastal

town of Great Yarmouth he met Mary Hunt and they married at St Nicholas's Church

on the 5th of May 1805. Initially, the couple lived in Great Yarmouth where

their first child was born but sadly died within a few weeks. By 1807 they had

moved to the village of Loddon where they had three children. It is not known

what form of work Thomas undertook in Loddon but by 1812 he had made his mind up

to go to sea and joined the Honourable East India Company as a Ship's

Steward on a wage of £2 a month. In sole charge of the ship's provisions, it

was a position of some responsibility. Mary moved back to Great Yarmouth,

probably with her parents, where she had three more children.

First Voyage

Thomas's first voyage, at the age of 31, was to India aboard the 614 Ton

'Alexander' (built in Liverpool around 1803 and similar to that pictured on the

right). The ship, under the command of Captain Charles Hazell Newell, left

Portsmouth on the 4th June 1812, stopped briefly in Madeira and arrived in

Calcutta on the 28th November (a voyage of almost 6 months!). The 'Alexander'

left Kedgeree at the mouth of the Ganges on the 19th January 1813, stopped at

Benkulen in Sumatra, where the East India Company had a pepper factory, Saint

Helena in the South Atlantic and finally arrived in the River Thames at

Blackwall on the 14th August 1813.

Eight months later, on the 11th April 1814, the 'Alexander' sailed again

for Madras and Bengal. This time Thomas appears in the crew list as 'Cooper and

Steward'. Unusually, the Journal for this voyage only records the

outbound leg, ending on the 9th October 1814 in Calcutta. It also carries the

following declaration ' This is to certify that this is the Original Journal of

the late Captain C H Newell deceased'. During a stop on the return voyage, at

Point de Galle (SW Ceylon), a fire broke out out on board a nearby ship

the 'Bengal'. Captain Newell died whilst helping to fight this fire but the

'Bengal' was lost. The 'Alexander' finally arrived back in England on the 25th

June 1815 under the command of Captain Henry Cobb.

The next two voyages that Thomas made were both bound for China aboard the

larger 1200 Ton 'Cabalva'. The first appears to have been uneventful but the

second was full of drama and ended in disaster.

The Loss of

the Cabalva

On the morning of the 14th April 1818, the 'Cabalva', in company with another

East Indiaman the 'Lady Melville', set sail from Gravesend bound for Canton. The

ship's company, commanded by Captain James Dalrymple, consisted altogether of

130 men; including six officers, a surgeon, the ship's steward (Thomas), seven

midshipmen, the captain's servant and one passenger. Under the guidance of an

old and experienced pilot and with favourable winds, the ship made good progress

through the Channel. However, at 11am on the 17th of April, just SSW of the Ower-light

ship near Portsmouth, the 'Cabalva' ran aground. The pilot was obviously

shocked, grew pale and clearly feared for his livelihood but had the presence of

mind to order the wheel to be put a-port, allowing the ship to gain sea-room. An

examination of the vessel revealed that there was nine inches of water in the

well. The Captain discussed with his officers whether to proceed, or go into

port to get the ship caulked. The decision was to proceed and the dejected pilot

was put ashore.

After several days at sea, the leak increased to

fourteen inches an hour so the pumps had to be manned day and night. At the Cape

of Good Hope, the 'Cabalva' fell in with the Honourable Company's ship the 'Scalesby

Castle' from whom they learned that the Ower-light ship had been found to have

drifted several miles in shore, by which intelligence the enigma was solved and

the pilot, captain and crew cleared of any negligence. The captain also learned

that his wife had safely given birth to a little girl. Some days later they

encountered a gale and were separated from the other two ships. The pounding the

ship received in the gale caused the leak to increase to twenty inches an hour

and so the decision was taken to divert to Bombay and have the ship caulked. The

hands at the pumps were doubled and the officers commanded not to carry too much

sail, lest the ship be strained and leak increased.

On Tuesday the 7th of July, at four o'clock in

the morning, the second officer ordered that look outs be posted on the

fore-yards, as the ships position and course were dubious. The wind was brisk

but not heavy and the 'Cabalva', with the wind on her quarter, cut her way

majestically through the dusky waves at a modest 7 knots. Apart from the seas

breaking on the bow, the only sounds were the snoring of those asleep, the steps

of the officers walking the deck and the occasional doleful cry of birds flying

above - suddenly the men stationed aloft shouted out repeatedly "Breakers -

breakers on the larboard-bow! hard a-port! hard a-port! Too late! All is lost!

hard a-port!" The helm was thrown a-port and the vessel rounded to, glanced

for a few seconds over the rocky bottom and then struck with great force

smashing the hull. One of the men on the fore-yard arm was thrown down and was

either dashed to pieces or carried away by the waves. Still with much sail, the

vessel heeled violently from side to side. The captain shouted "Cut away

the main mast! down with the foremast! stand clear the masts!" Everyone

sought refuge whilst the task was accomplished with hatchets and similar

instruments until the masts gave way and fell with all their tackling into the

foaming ocean. No sooner are the masts cut away in a sinking ship, than the

feeling of perfect equality arises amongst her crew.

As a glorious sunrise brought the dawn, efforts

were made to float the large cutter - no sooner had this been achieved than some

of the youngest and stronger crew climbed in, pushing aside weaker and injured

wretches. Captain Dalrymple declined going off in this boat; but the sworn

officers (except the second) all jumped on board her and the boat made directly

for the reef. The second officer, surgeon, several mid-shipmen and crew later

swam ashore with the aid of cork jackets. The party in the cutter had no oars

and were using a rope tied to the wreck to control their drift towards the reef

about 150 yards away - unfortunately a tremendous surf broke over them and threw

every soul clean out and dashed them against the rocks.

For some time after, individuals designed their

own plans for getting ashore. One sailor went to the captain's cabin and drank a

bottle of brandy before cheerfully jumping over the side and succeeded in

swimming ashore, aided by a bale of cloth which he steered to protect him from

the rocks. Another group of about twenty sailors and the captain created a raft

from the booms. This was successfully launched and supported their swim to the

shore but as they approached the rocks they too encountered the surf and

everyone was thrown on to the reef to be battered further by subsequent

breakers. The captain and several others disappeared into the sea and were

drowned, many broke arms and legs and had nasty cuts.

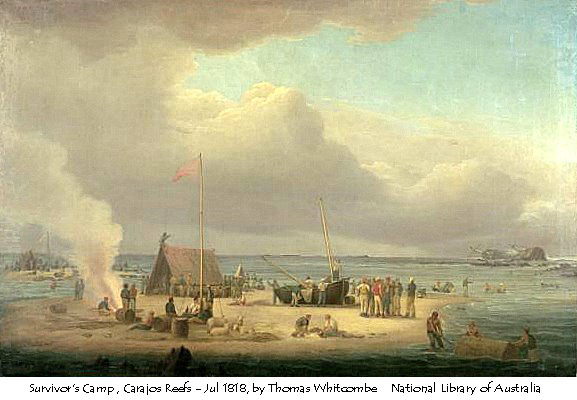

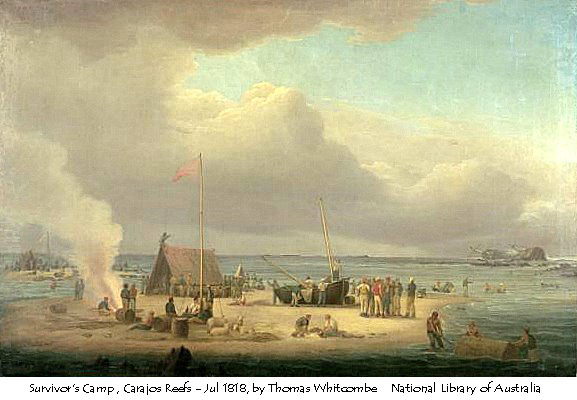

The coral reef, which was almost covered with

water when the ship struck, appeared to rise out of the sea as the tide ebbed

and was strewn with a confused heap of articles - casks of wine, beer and

brandy; trunks and bales, some containing gold, silver and fine glass; fine

English muslin and Irish linen. Disorder reigned, not only amongst the debris

but worst among the survivors. The seamen, almost frantic, grew brutally

selfish, they took themselves to the beer and spirits, fought each other over

the gold, cut open bales and dressed themselves in the most grotesque and

ridiculous garbs. There was an abundance of port and spirits on the reef but

little fresh water and no food.

Three or four miles to the north-west were a

group of sand-banks, only three feet above the surface of the sea but likely to

afford better protection than the reefs - so began a gradual migration towards

them, with many sailors carrying several bottles of spirits. No one had shoes,

so feet became badly lacerated walking and wading across the coral. The next

day, officers tried to persuade parties of men to return to the wreck to see if

any victuals and water-casks could be saved before the ship went totally to

pieces but to no avail, there was hardly a sober man amongst them. Fortunately,

some later arrivals had brought with them six or seven pieces of pork, three

casks of fresh water which, together with a young shark that had been caught and

some lobsters, produced a dinner for 120 men. When

the tide came in that afternoon, it set so strong that the rocks near the ship

were completely inundated and the wind drove everything light and floatable over

towards the sand banks. Although everything  was

gathered up, there was little of practical use except for a powder keg that was

completely dry. Using some powder, remnants of linen and driftwood a comfortable

fire was lit. That evening a tent was constructed from wooden spars covered with

fine English linen but could scarcely accommodate more than fifty men.

was

gathered up, there was little of practical use except for a powder keg that was

completely dry. Using some powder, remnants of linen and driftwood a comfortable

fire was lit. That evening a tent was constructed from wooden spars covered with

fine English linen but could scarcely accommodate more than fifty men.

Whilst many of the more prudent and skilful men

worked tirelessly to better the situation, there was a large faction who held to

the old motto of 'every man for himself' and these spent most of the time

drinking and sleeping. It was good luck that many casks had been washed up on a

nearby sandbank and so this drunken band established their settlement on this

bank which soon became referred to as 'Beer Island'. Further visits were made to

the ship, which yielded more provisions including six live pigs and five live

sheep, as well as several drowned animals and fowl. The ships large cutter,

although damaged, was retrieved and hauled back three miles to the sand bank.

The carpenter and the sail-maker (whose

bag containing needles and other articles providentially washed up on the sand)

proceeded without delay to repair the large cutter. Other searches turned up

navigation items such as a quadrant, a sextant, log-reel, chronometers and a

Nautical Guide to the East Indies but no compass could be found. With the

assistance of these instruments, the exact location and name of the reef was

ascertained as was the fact that the nearest inhabited country was the island of

St. Mauritius some 250 miles SSW. A plan was developed to send out the large

cutter with an officer and some sailors to reach Mauritius, Bourbon or failing

these, Madagascar.

At first light on Tuesday 14th of July, exactly

a week after striking the reef, the cutter was launched and quickly caught the

breeze. The crew, weakened through the lack of food and the strong motion of the

small boat, all became extremely sea-sick, which added to the toil of this

dangerous voyage. Cloud and rain prevented a noon observation on that first day

but later glimpses of the sun, when it occasionally burst through, indicated

that they were running a SSW course at the rate of five to six knots. After a

troubled night, with no sleep, the next dawn brought a bright and cloudless sky

- at noon an accurate observation was possible. The weather deteriorated and

squalls frequently rose to a prodigious height demanding great effort and skill

from the helmsman, whilst three hands were employed in continuous baling. The

trailing log was lost and that evening the sun did not set clear, so their

position was based upon much guesswork. It wasn't until two o'clock that

the sky cleared and a bearing could be taken on the southern cross which showed

them to be considerably off-course and in danger of not being able to make the

island. However, not long after dawn, land was spotted and soon determined to be

Round Island close to but leeward of Mauritius. It was essential to work to

windward but the squalls forced constant easing of the sails. Having got to a

position some fourteen miles leeward of Port Louis, they found they could not

make any way to windward and so took in the sails and attempted to row. Luckily

a shift in the wind after sunset allowed them to work into shore under sail but,

ignorant of the entrance to Port Louis, they elected to anchor in nine feet of

water, close under land, until the dawn. The next morning they were able to row

into Port Louis to the surprise and amazement of other sailors on ships in the

port.

The agent of the East India Company was

immediately informed of the wreck and it's position, and within an hour, two

British navy ships, the frigate 'Magicienne' and the brig 'Challenger', were

dispatched to rescue the remaining survivors. On Sunday the 20th July, the

look-out on the mast head of the 'Magicienne' was heard to shout 'Breakers on

the larboard bow!' Hard a-port!' but this time it did not herald danger but the

discovery of the 'Cabalva' and the tents on the sand-banks.

Whilst the 'Magicienne' remained anchored at the

sand bank for several days, in order to salvage any of the 'Cabalva's' cargo,

the 'Challenger' carried the ship-wrecked crew back to Mauritius and distributed

them on board several vessels which lay in Port Louis harbour. Some took up new

engagements and dispersed to all quarters of the globe, others took their

passage back to England. Seventeen men, including Captain Dalrymple, lost their

lives and the financial loss of the ship and it's cargo to the East India

Company (who never insured) was estimated to be £350,000.

Was Thomas in the 'Beer Island' gang or one of

the more industrious survivors on the sand bank? Probably the latter, as he

continued to serve with the Honourable East India Company as a Ship's Steward.

To read the full 65 page narrative written by the Sixth Mate Mr C W Francken click

here. It is a remarkable and detailed account, well worth reading in

full.

Soon

back at work

Soon

back at work

The shipwreck clearly didn't deter Thomas from a sea going life, because the

following year, on the 3rd May 1819, he left England for the first of three

voyages, as Ship's Steward, aboard the 1318 Ton 'General Kyd' all bound

for China and under the command of Captain Alexander Nairne. The last of these

arriving back in England at Blackwall on the 28th March 1824.

There is then a gap of 27 months before his next

known voyage begins on the 18th July 1826. I have searched for him in the

crew lists of the most likely 18 (out of 31) HEIC ships that he could have

served on during this time. This might be because he was in prison! There is an

entry in the discharge books for the Fleet Prison in London, for the release of

a Thomas Blunderfield on the the 27th May 1825.

Whilst researching the ship's Journal for his

next voyage, aboard the 1331 Ton 'Winchelsea', it was a surprise to find two

Thomas Blunderfields in the crew list. His eldest son Thomas, aged 15 years, was

listed as a Boatswain's Servant This first voyage with his son was directly to

Whampoa in China and lasted just under 11 months.

Two-Quid a

Month

There mustn't have been inflation at that time, since Thomas's pay was the same

in 1828 as it was when he started in 1812 - £2 per month. The ship's Captain

was paid £10, the Surgeon £5, the Carpenter £4 (clearly an important job),

Ordinary Seamen £1-15s and boys just 10s per month. Wages were paid at the end

of the voyage, although some money could be advanced by the purser if needed in

foreign ports. The Ledgers and Pay Records survive for many of the voyages and

make interesting reading. For example, for the voyage aboard the 'General Kyd in

1821/2, he earned £39-8s-0d (for 19months and 21 days service). The

following deductions were then made: Imprest £4 (this would be the amount

advanced to Thomas during the voyage), Absence Paid His Attorney £6 (this is

not his lawyer but debts that had accumulated during his absence, for example

house rent, his family's food etc), Greenwich Hospital Duty 10s-6d. His ‘take

home’ pay amounted to £28-17s-6d).

Their last Voyage

In 1823, two new 1300 Ton ships had been ordered from the shipbuilders Wigram

& Green at Blackwall. The 'Edinburgh' was launched on the 9th November

1825 and the 'Abercrombie Robinson' on the 11th December 1825. They were

both owned by Henry Bonham and chartered by the East India Company for four

voyages each between 1825 and 1831.

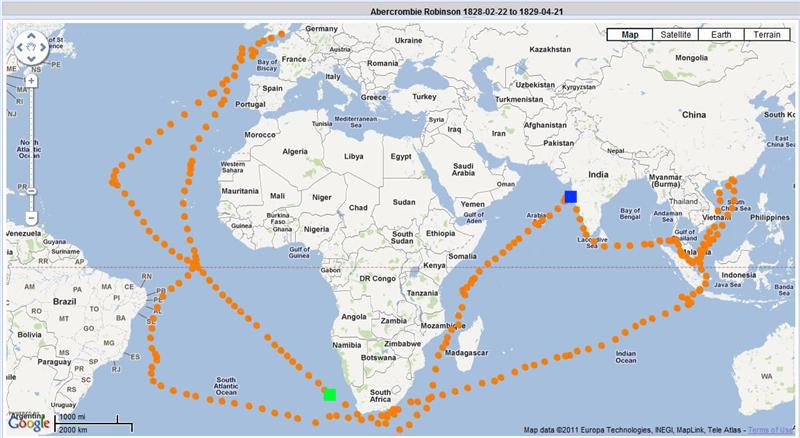

On the 22 February 1828, Thomas and his son left

England on board the 1331 Ton 'Abercrombie Robinson' bound for India and China

under the command of Captain John Innes. On this voyage, Thomas Junior was a

Servant to the Ship's Carpenter. After 14 weeks at sea, the ship arrived in

Bombay on the 4 June 1828 and stayed for several weeks. Sadly, just before the

ship left Bombay on the 11th August 1828, the following notes appear in the

ship's journal.

Saturday 9 Aug 1828 – Bombay. Departed this

life, Thomas Blunderfield, Carpenter’s Servant and Joseph Ellis, Gunners

Servant.

Sunday 10 Aug 1828 – Bombay. Sent the bodies of the deceased Thomas

Blunderfield and Joseph Ellis on shore for interment.

Monday 11 Aug 1828 – 2am Pilot left the ship.

Tuesday 12 Aug 1828 – Towards China. Cholera began to make it’s appearance

amongst the Ship’s Company in the course of the night – seven new men

attacked by this dreadful disease.

This must have been a dreadful blow to his

father, made worse by the fact that the ship left a few hours after his son's

body had been taken ashore for burial - was he even able to attend the burial?

The daily sick report around this time typically numbered 25 to 35. Deaths and

burials at sea were a daily occurrence and fumigation was frequent. However, by

early September the sick report was down to 6 or 7 per day but deaths were still

being recorded.

After a brief stop in Singapore, the ship

continued to China, arriving in Macau on the 23 September 1828. After a stay of

7 weeks, they set sail for England on the 13 December 1828, stopping for a

couple of days (including New Year's Eve) in Jakarta and in Saint Helena then

back to Southampton. Cholera was still present and on the 12 February 1829, two

days after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the following notes appear in the

ship's journal.

Thursday 12 Feb 1829 – Towards St Helena. At

3am, Thomas Blunderfield, Ship’s Steward and at 7am Robert Halpen, Armourer,

departed this life.

Friday 13 Feb 1829 – Towards St Helena. At 1am, committed the bodies of the

deceased Thomas Blunderfield and Robert Halpen to the Deep with the usual

Ceremony.

Saturday 14 Feb 1829 – Towards St Helena. Appointed Edward Allen, Ordinary

Seaman, to the station of Ship’s Steward.

From a ship's company of around 150, the journal

records that 55 men died or drowned during this voyage, one is even recorded as

having 'jumped overboard'.

When

sailors died at sea, either through disease or accident, the body was normally

buried at sea usually in pieces of weighted sailcloth. The master conducted the

ceremony before the crew and recorded the fact in the ship's log. In the Royal

Navy the dead were sewn into their hammocks which was weighted with round shot.

The sail-maker would put the last stitch through the dead man's nose to ensure

that he really was dead.

The ships of the Honourable East

India Company apparently kept better log-books, showing position, sea conditions

and weather, than the Navy did at the time. These are proving to be a valuable

source of information for climatologists researching historical weather patterns

and so the data has been published on the internet. The map above shows the

daily positions (at noon) of the 'Abercrombie Robinson' during the final voyage

of Thomas and his son - the blue square shows Bombay where Thomas (Junior) died

and the green square the ship's position at sea on the day that Thomas (Senior)

died.

A

Widow's Pension

In 1625 the East India Company

established the 'Poplar Fund', which was a mandatory pension scheme.

Company mariners of all ranks and rates paid tuppence,

later thruppence, in the pound from their pay. From this fund, temporary

or permanent relief, including widows’ pensions or admission to almhouses

was doled out frugally. Consequently, on the 13th May 1829,

Mary Blunderfield as the widow of a Ship's Steward was granted an annual pension

of £8 during her widowhood and £3 for each child under the age of 21 years

(five at that date) until they reached a prescribed age. Mary did not remarry

and in October 1843 petitioned Trinity House for an additional pension on the

grounds that the £8 she received from India House was not sufficient to support

her. Mary died in 1858 aged 78 years.

Known Voyages

From the detailed records that

were kept by the East India Company, it has been possible to determine the ships

that Thomas sailed on and the periods he was away from home (quite a lot!). The

sailing dates of the East Indiamen were arranged so that the China ships could

take the S.W. monsoon up the coast and the N.E. for the return passage, thus an

average voyage took about 18 months.

In

the following voyage summaries, the location 'Downs' appears frequently. This is

a shallow area of sea close to Deal in Kent which provided an anchorage and

shelter from SW Gales before ships entered the English Channel. Deal also had a

time-ball tower that enabled ships to set their marine chronometers.

Whampoa is an Anglicisation of the Chinese "Huangpu", it is on the

Canton River, upstream from Macau and just downstream from Guangzhou (Canton).

Macau is the first port near the entrance to the Canton River from the South

China Sea. The other location that perhaps needs explanation is 'Second Bar' -

this was a sand bar about 20 miles down river from Whampoa..

It

is interesting to see that Thomas visited St Helena twice, perhaps three times,

between 1815 and 1821 when Napoleon was exiled there. The ships usually stayed

for about a week to unload stores and take on water and other provisions.

'Alexander'

1812/13 Bengal and Benkulen (Capt. Charles Hazell Newell).

4 Jun 1812 Portsmouth - 18 Jun 1812 Madeira - 28 Nov 1812 Calcutta -

19 Jan 1813 Kedgeree - 4 Mar 1813 Benkulen - 31 May 1813 St Helena - 14 Aug 1813

Blackwall.

1814/15

Bengal (Capt. Charles Hazell Newell and Capt. Henry Cobb).

9 Apr 1814 Portsmouth - 26 May 1814 Madeira – 19 Sep 1814 Madras - 9 Oct 1814

Bengal ….. voyage ended 25 Jun 1815

'Cabalva'

1816/17 Bombay and China (Capt. John Hine)

23 Jan 1816 Downs - 15 May 1816 Bombay - 13 Jul 1816 Penang - 26 Jul 1816

Malacca - 19 Aug 1816 Whampoa - 20 Oct 1816 Second Bar - 2 Mar 1817 St Helena -

6 May 1817 Gravesend.

1818/** China (Capt. James Dalrymple)

16 Apr 1818 Downs - wrecked on Cadargos Shoals, Carajos Reefs (about 250 miles

NW of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean) 7 Jul 1818 - Captain, Surgeon's Mate and 15

crew drowned.

'General Kyd'

1819/20 Madras and China (Capt.

Alexander Nairne)

1 Mar 1819 Portsmouth - 12 Jun 1819 Madras - 23 Aug 1819 Penang - 16 Sep

1819 Malacca - 19 Oct 1819 Whampoa - 16 Dec 1819 Second Bar - 20 Apr 1820 St

Helena - 19 Jun 1820 Downs.

1821/22 Bengal and China (Capt. Alexander

Nairne)

23 Jan 1821 Downs - 29 Aug 1822 Moorings

1823/24 Bengal and China (Capt. Alexander

Nairne)

8 Jan 1823 Downs - 10 May 1823 New Anchorage - 2 Aug 1823 Penang - 20 Aug

1823 Singapore - 3 Oct 1823 Whampoa - 13 Nov 1823 Second Bar - 7 Feb 1824 St

Helena - 28 Mar 1824 Blackwall

******* Here there is a gap of over two years where there are no records of him

being at sea. This might be because he was in prison! There is an entry in the

discharge books for the Fleet Prison in London, for the release of a Thomas

Blunderfield on the the 27th May 1825.

'Winchelsea'

1826/27 China (Capt. Roger B Everest)

18 Jul 1826 Downs - 24 Dec 1826 Whampoa - 11 Feb 1827 Second Bar - 25 Apr 1827

St Helena - 3 Jun 1827 Downs

'Abercrombie Robinson'

Named

after the then Deputy Director (later the Chairman) of the Honourable East India

Company Sir George Abercrombie Robinson.

1828/9 Bombay and China (Capt John Innes)

21 Feb 1828 Downs - 5 Jun 1828 Bombay - 3 Sep 1828 Malacca - 26 Sep 1828 Whampoa

- 12 Dec 1828 Macau - 22 Feb 1829 St Helena - 20 Apr 1829 Blackwall. Both Thomas

and his son died during this voyage.

was

gathered up, there was little of practical use except for a powder keg that was

completely dry. Using some powder, remnants of linen and driftwood a comfortable

fire was lit. That evening a tent was constructed from wooden spars covered with

fine English linen but could scarcely accommodate more than fifty men.

was

gathered up, there was little of practical use except for a powder keg that was

completely dry. Using some powder, remnants of linen and driftwood a comfortable

fire was lit. That evening a tent was constructed from wooden spars covered with

fine English linen but could scarcely accommodate more than fifty men. Soon

back at work

Soon

back at work